Principle 6: Appropriate use of diversification

- W. Allen Wallace

- Apr 4, 2019

- 8 min read

Diversification, in the sense that we are interested, is defined by the NASDAQ Online Glossary as “Investing in different asset classes and in securities of many issuers in an attempt to reduce overall investment risk and to avoid damaging a portfolio's performance by the poor performance of a single security, industry, or country”. Sounds reasonable, but surely, we are not expected to believe that an indiscriminate amorphous blob of diversification is the right amount.

Dear Family, Friends, and Clients,

Discussing diversification in the long shadow of a moderating term like “carefully” may seem anathema to certain investment fanatics. As Peter Bernstein noted: “Indeed, diversification has become a veritable religion among investors”.[1] In fact, based on one modern translation of Ecclesiastes, it says so right there in The Bible:

1 Send your grain across the seas, and in time, profits will flow back to you. 2 But divide your investments among many places, for you do not know what risks might lie ahead. - Ecclesiastes 11:1-2 (New Living Translation)

Diversification, in the sense that we are interested, is defined by the NASDAQ Online Glossary as “Investing in different asset classes and in securities of many issuers in an attempt to reduce overall investment risk and to avoid damaging a portfolio's performance by the poor performance of a single security, industry, or country”. Sounds reasonable, but surely, we are not expected to believe that an indiscriminate amorphous blob of diversification is the right amount.

The conundrum we face is clearly a matter of degree, not kind. As Swiss physician, alchemist, and astrologer Paracelsus is credited with expressing, “All things are poison, and nothing is without poison, the dosage alone makes it so a thing is not a poison." The purpose of Principle 6 is laying the groundwork for determining the correct prescription to help you realize your goals, because as surely as too much oxygen or water can be harmful, diversification is a medicine most wisely used in moderation.

Perhaps in unpackaging this puzzle we should, in the words of Lewis Carrol, “begin at the beginning”. Modern Finance began in 1952 with the publication of Portfolio Selection, by Harry Markowitz. The intended goal is to maximize performance, defined as annual return, or the increase in price from January 1 to December 31, plus dividends, while minimizing risk, which is defined as Standard Deviation. Since investors are “risk averse” they attempt to find efficient portfolios which are points on an efficient frontier that maximize return for a given amount of risk. Past prices and fluctuations are used to make a forecast of future returns and fluctuations. In order to determine the mean expected return and standard deviation of a portfolio of securities their covariances, or how they have moved together in the past, are used to predict future correlation. All of this is thrown into a computer and it calculates an elegant expected portfolio return and standard deviation.[2]

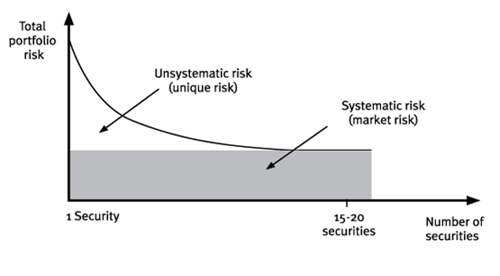

Standard Deviation, or investment risk, in modern financial jargon, can be broken down into two major components. Systematic Risk is the risk attributable to investing in general; it is measured by the Greek letter β (beta). It is undiversifiable, and can be caused by changes in interest rates, recessions, wars, political scandals, or other triggers of mass psychology. Unsystematic Risk, or Specific Risk, is the set of risks attributable to a single company or industry and could be caused by changing consumer tastes, poor management, CEO malfeasance, or a host of other dreadful consequences encountered in the course of running a business. Unsystematic Risk is diversifiable, and according to the long-beards of finance, investors should not be compensated for Unsystematic Risk because it is unnecessary. Harry Markowitz quipped in Portfolio Selection: “If security returns were not correlated, diversification could eliminate risk”.[2]

The Professors of Finance are gluttons for diversification. Harry Markowitz assures us that diversification is "the only free lunch in finance." But we know that nothing is really free, so what do we get for our money? If Risk, defined as Standard Deviation, is comprised of Systematic and Unsystematic Risk, and Unsystematic Risk is diversifiable to zero, then under this rubric, a widely diversified portfolio’s risk is equal to Systematic Risk. Standard Deviation is defined as squared deviations from the mean, or expected return, which in English means the amount we can expect our return to be below or above the expected return 67% of the time. If we diversify away our chances of unsystematic underperformance, surely, we also diversify away our opportunities for outperformance. It seems that risk, as defined in these terms, is not necessarily a bad thing, especially if we can influence, to a certain extent, whether our risk is somewhat positive or somewhat negative. Perhaps if we carefully select securities trading at a measurable discount to fair value, with able and competent management, in an industry with favorable prospects, and in a business with a durable competitive advantage, we should be cheering for more risk!

The rub lies in the definition of efficient portfolios. The efficient portfolio is defined as the maximum expected return for the lowest risk, defined as Standard Deviation. So, in other words, minimize the opportunity to outperform in order to decrease the likelihood to underperform, which is why legendary investor John Neff said: “Obsession with broad diversification is the sure road to mediocrity.” If efficiency encompasses doing things right, but effectiveness encompasses doing the right things, put me in the camp of those in search of effective portfolios.[5] To invert the old proverb, anything not worth doing, is not worth doing well.

As we discussed in Principle 3 “Minimizing volatility in the form of annual deviations from the mean is not our goal, and not how we define risk. We accept volatility as a normal part of investing”- especially if we never speculate, always demand a margin of safety, and maintain adequate liquidity. These complementary principles allow us the flexibility to collect rent for accepting the Unsystematic Risk that comes from not owning a little bit of every security. Economist John Maynard Keynes wrote to F.C. Scott in 1934, “I get more and more convinced that the right method in investment is to put fairly large sums into enterprises which one thinks one knows something about and in the management of which one thoroughly believes. It is a mistake to think that one limits one’s risk by spreading too much between enterprises about which one knows little and has no reason for special confidence.” [3]

Simply making the case that infinite diversification is unhelpful, is unhelpful. There lies a great bit of space between a little and a lot. Warren Buffett went so far as to say that "Wide diversification is only required when investors do not understand what they are doing”. With this in mind, our process demands making enough independent decisions to leave the possibility of reaping the rewards of correct processes, but not so many that the laws of statistics and luck, either good or bad, dominate. Or as Keynes put it: “The social object of skilled investment should be to defeat the dark forces of time and ignorance which envelop our future”.[4] Maintaining humility, we understand that the future is opaque, and that we are charged with ensuring that your assets last as long you need them. We diversify based on your individual goals, risk tolerance and time-frame. If you need to limit volatility to meet your monthly expenses, wider diversification is required than if you are 30 years old and saving regularly. If price fluctuations keep you up at night, we will work to build a portfolio that helps you sleep.

Having established the case that some diversification is good, but there are diminishing returns to its effectiveness, we will now attempt to zero in on something closer to the general prescription we seek. While each portfolio will be customized to the needs of the individual, a baseline can be established based on the facts. John L. Evans and Stephen H. Archer set out to explore exactly this question in their 1968 Journal of Finance article “Diversification and the Reduction of Dispersion: An Empirical Analysis”. The paper examined “the rate at which the variation of returns for randomly selected portfolios is reduced as a function of the number of securities included in the portfolio.” While it would tickle me to drone on boringly about the mathematics of the paper, suffice it to say that 19 was the answer. The additional benefits of diversification in a portfolio of randomly selected securities begins a terminal decline at 19 securities according to their research.[7]

So how many securities do your equity mutual funds own? Travis Sapp (from Iowa State, no less) and Xuemin Yan, found that the average mutual fund has 90 holdings, and that the 20th percentile of most diversified funds held 228 stocks.[8] In a portfolio of 10 mutual funds, with non-overlapping holdings, on average, this would be exposure to 900 unique stocks. With this number of holdings, paying for professional management could be argued to be superfluous when an index fund could be purchased almost for free, with exposure to less securities. There is very little skill involved in picking the best 900 stocks in a market comprised of approximately 3,600 listed securities.[9]

At Basepoint Wealth, one of our core mutual fund selection criteria for equity mutual funds is concentrated holding; we target equity mutual funds with between 20-40 securities. Taken together, the five core funds in our current portfolio, consisting of Large, Mid, and Small sized companies totals 143 positions, or an average of 28.6 per fund. While this is higher than the magic number found in the above referenced study, it provides assurance that all securities are purchased based on fundamental analysis and that our managers “think they know something about” each and every holding. All our current core equity fund managers utilize fundamental analysis to determine an estimated fair value for the businesses that they own, and purchase businesses at discounts to their estimate of fair value. It is our contention that even though our short-term performance may be slightly more volatile than a more widely diversified portfolio, over long periods of time, our approach puts us in a position to generate higher returns. We will maintain adequate liquidity to ensure that your cash flow needs are met, and to have additional capital to commit when we experience negative fluctuations.

It is logical to wonder why the world is awash in infinite diversification and a refusal to, at minimum, check the price in relation to value of the assets that are purchased. The answer to why the bulk of portfolios are managed this way is simple: conventional wisdom. “Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.”[4] It’s warmer in the center of the pack, and it presents a great deal of career risk for an individual to swim against the tide when common sense appears to be countered by smart people armed with math.

If asset prices did not swing wildly about, we would not be tempted to apply statistics to the squiggles on charts they leave behind in an attempt to predict future price movements. Contrarily, if businesses were valued purely based on cash flows and current interest rates, instead of opinion and mass psychology, the concerted effort we apply to attain higher returns would be in vain. It is the failure of logic in the system that allows mispriced securities to exist. So, for this injection of human nature and cognitive dissonance into the markets, we are ever grateful.

Our mandate is to help you maximize your economic value over a lifetime, and in many cases longer. We do this by helping you develop clear goals, utilizing principles that have been proven over many decades, not falling victim to conventional wisdom, and not substituting math for common sense. Together we will chart progress and continue to refine and expand your goals, and do our best to preserve your capital, earn a good return adjusted for inflation, and take advantage of non-investment strategies like tax planning, retirement planning, estate planning and other strategies to maximize your net economic benefit over the lifetime of your family. We appreciate the trust that you give us, we will work hard to maintain it.

Warm Regards,

Allen

W. Allen Wallace, CFA, CPA/PFS, CFP®

Chief Investment Officer

Works Cited:

Bernstein, P. L. (1998). Against the gods the remarkable story of risk. New York: Wiley.

Markowitz, Harry M. Portfolio Selection. 1967.

Benello, Allen C.; van Biema, Michael; Carlisle, Tobias E. (2016). Concentrated Investing. Wiley.

Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest and money. New York: Harcourt, Brace.

Drucker, P. (2018). The Effective Executive. Saint Louis: Routledge.

Evans, J. L., & Archer, S. H. (1968). Diversification and the Reduction of Dispersion: An Empirical Analysis. The Journal of Finance,23(5), 761. doi:10.2307/2325905

Kaplan Financial Limited. (n.d.). ACCAPEDIA. Retrieved from http://kfknowledgebank.kaplan.co.uk/KFKB/Wiki Pages/The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM).aspx

Sapp, T., & Yan, X. (. (2008). Security Concentration and Active Fund Management: Do Focused Funds Offer Superior Performance? The Financial Review,43(1), 27-49. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6288.2007.00185.x

Rasmussen, C. (2017, October 25). Where have all the public companies gone? Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2017/10/25/where-have-all-the-public-companies-gone.html

Comments